Wilderness Adventure: Wolf Trapping

Wilderness Adventure: Wolf Trapping

By Rose Abdulkareem

My fiancé, Josh, and I refer to wolves as “tundra ghosts” because while we hear their howls and find sign of their passing (caribou kills, tracks, scat, etc.), we rarely see them. That said, packs do run the snow machine trails along our traplines, sometimes in great numbers, and we are always eager for an opportunity to take on such a worthy adversary.

Work keeps us busy year-round, yet we still manage to spend a good portion of our free-time outdoors. The dark and frigid Alaskan winters don’t provide many good reasons to venture out, but we would lose our minds if we stayed imprisoned indoors four months out of the year. Our remedy for the madness of cabin fever is to go trapping. Marten, lynx, coyote, wolf, and wolverine bring good money, but trapping is our escape, a challenge that brings us closer together and keeps our brains engaged.

Wolves are incredibly intelligent, making them our holy grail. When they outwit us, we are left with the promise of “maybe next time.” That promise is what pushes us to continue the crusade. We repeatedly make what we think are perfect sets for the alpha canines, only to be disappointed nine times out of ten as they float right by.

But we do have our days …

One morning in early January, we set out for our nearest trapping cabin, checking traps, luring and resetting as needed along the way. We arrived at the primitive shelter in early afternoon, just in time to watch a black sky burst into the vibrant colors only a midday Arctic winter sunrise can bring.

We parked our snow machines in front of the cabin, scanning the frozen river and pond for caribou, which often linger in the area. No caribou were to be found, so we started unloading the sleds. In the crisp silence, Josh heard a muffled scuffling coming from the snow-laden spruce across the river, and we stopped unpacking to go investigate.

The banks are steep by the cabin, so we had to backtrack along the trail to a point where the slope was manageable on snow machines. Once on the other side, the trail dumped us at the beginning of tussock-filled flats that are void of trees, save for one lone sapling.

On our last visit at the cabin, we saw where wolves had been using the skinny little tree as a marking post, providing an ideal opportunity for a set. With no better way to sufficiently anchor a foothold, we had cut a larger tree and lugged it into position to serve as a drag with a trap attached at each end. One of the traps was bedded directly where a wolf would stand to mark the sapling. We figured a wolf would be strong enough to pull the tree drag when it bolted, but then it would entangle in the brush.

The drag was missing, and we stared at marks leading into the trees along the riverbank. Glimpses of movement revealed a wolf pack fleeing from our approach, and a black wolf with a speckled-grey muzzle waited in the trap, growling and baring its teeth as we neared. The old wolf had broken several teeth on the cold trap steel. Josh dispatched the senior canine without delay. It was clear that he had been in rough shape before he wound up in the trap, both gaunt and mangy. What should have been a prime winter coat was instead coarse and thin; a half-healed gash torn through the back of the neck. While teeth had been broken on the trap, considerable more had been fractured previously.

Tracks revealed at least seven and maybe eight other wolves, and another had been caught temporarily in the second trap. There was a small amount of blood on the jaws. As I knelt to release the paw of the wolf that hadn’t escaped, a ghostly chorus of howls rose from the tundra where the rest of the pack had regrouped.

Since we were already across the river, we decided to check the traps we had set on that side of the valley. After a mile of navigating tussocks, we arrived at the first marten set, a small ground cubby sheltered by a wooden A-frame with a Conibear at the entrance and bait at the rear. This trap was snapped with a bit of bloodied wax paper stuck inside.

We don’t use wax paper with Conibears, only for bedding foothold traps, and the only place we had set footholds was at the wolf drag. Apparently, the wolf that managed to escape had then stuck its paw in this marten set, snapping a second trap on the same foot.

With all sets checked, we made our way back to the cold cabin, lamenting not having taken a few minutes to start a fire in the barrel stove. Along the wooded trail that led back across the river, we found ample evidence that at some point within the past few days a herd of caribou had come through, no doubt followed by the wolf pack.

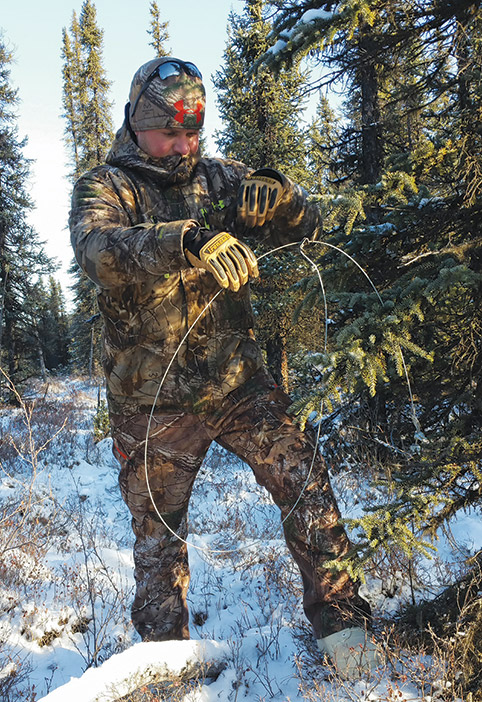

Josh had previously saturated the area with snares. Hidden in the trails beside every tree, multiple snares make the optimal gang set for wolves, camouflaged and quickly deadly with minimal fur damage. Yet the wolves’ eyes are too sharp to be fooled often, and they usually avoid our loops.

We dismounted our snow machines and set out in opposite directions to check these snares. Then I heard Josh yell. He was standing over a snare that held one of the biggest wolves either of us had ever seen. Even curled and frozen, the wolf eclipsed Josh in length and probably weighed nearly as much as he did. The canine was so massive we had to leave it at the site until the next day because the partially loaded sled would not hold such a catch

The alpha male demanded an entire toboggan all his own.

After a restful night in the cabin, we were up early to continue checking the far reaches of our trapline. The wolves had been busy along our trails, and our fingers were crossed. We made a beeline for the main river, opting to check the outer loops on the way back.

At the river, the machines had to be carefully maneuvered down sheer banks; from there, we drove on the ice for several miles before turning to the flats on the opposite side. Animals also travel the frozen waterways, and we had a number of sets positioned. Only one yielded a catch, but it was quite a catch.

We had made two gang sets, one on each side of the bend where we descended. One was a series of Conibears ranging in various sizes, arranged leading up to a fallen tree with a large chunk of bait. The purpose of multiple bodygrips was to filter out smaller catches. Lynx was the intended target, and these smaller animals often snap traps and steal baits.

Already eagerly anticipating that set, we saw something even better than expected in the large Conibear: a wolverine. One of the smaller body traps leading to the wolverine held a squirrel, and I was pleased to see that Josh’s forethought may very well have enabled us to catch one of the most valuable furbearers.

While Josh worked at removing the traps from the tree, I wandered upriver to check more sets, following the tracks of that same wolverine. Before getting caught, the wolverine had set off each of the smaller traps in progression, stealing the bait in what had no doubt been a delightful buffet. There were numerous other tracks, and I was briefly annoyed by how many other catches we missed because of the greedy wolverine. But we got him, so my pique fizzled out rather quickly.

By the time I returned Josh had replaced the Conibears with new ones, and off we went to check the remainder of the line.

It was mid afternoon by the time we returned to the river crossing. We checked the large Conibear set again, and this time it held a prime marten. Out of traps to reconstruct the set, we opted to return the following day in order to do this. We did manage to check a few side trails on the way back, all traps empty.

The next day, while making our way back to the river, we were once again side-tracked at one of Josh’s wolf gang sets. In the middle of the snow machine trail he had placed a very obvious foothold, purpose being to alert the wolves to a trap, thereby forcing them off the trail to weave through the trees. Snares were strategically placed in a spiral pattern extending out from the foothold. A bit more in-depth than simply placing as many snares as possible, but our gang sets play on wolf behavior rather than luck.

We had caught other wolves in similar sets, but not today. The wolf pack had reacted as anticipated, but the result was not as anticipated. Two had been caught in the snares. But the locks had failed, allowing them to escape. Our resident wolves tend to be larger and stronger than average.

We packed up and headed for home the following day. I was eagerly anticipating a “curiosity” set I had made on our way to the cabin.

Over the years, I have noticed that wolves are always interested in anything dropped on the trail, and over that rough terrain, items often bounce out of the sled. In the middle of the flats nearest the mountains, about halfway between home and the first trapping cabin, I had placed a broken camping chair in the middle of the trail, surrounded by foothold traps. Considering all of the wolf traffic, surely my set had caught one.

That confidence in my own abilities was met with a reality check. A trail camera at the site showed that wolves had, indeed, been through the set, even stopping to sniff the chair. But none of the traps had snapped even though there were prints right on top of several of them.

Daytime warming by the sun’s brief rays had been enough to melt the snow covering the traps, and when Arctic cold returned in the evening, they froze over. Another lesson learned the hard way.

Yet it had been an eminently satisfying trip, yielding a variety of valuable fur. The fact that we had managed to collect a pair of tundra ghosts made it extra special. Other times we have brought home more fur, but outsmarting wolves is especially satisfying.