Wilderness Adventure: In Wild Bear Country

Wilderness Adventure: In Wild Bear Country

By Brian Hood

How can you tell the difference between black bear scat and grizzly bear scat? Black bear scat has berries in it. Scat with those little bells hikers wear, and a light whiff of pepper spray, was left by a grizzly. Our outfitter decides to break the ice with that old joke as we meet for the first time over breakfast. We are heading out to hunt elk in the Thoroughfare, well-known grizzly country just southeast of Yellowstone National Park.

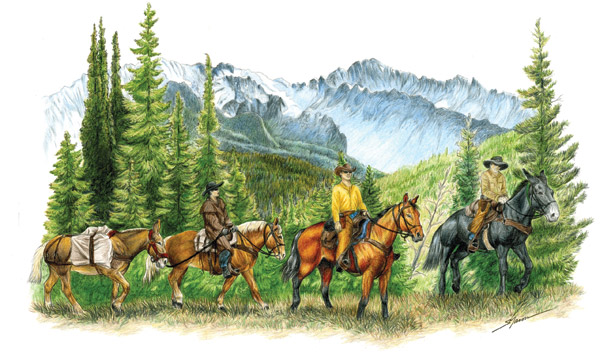

A 45-minute truck ride takes us to the trailhead, where we saddle up. It’s 70 degrees and sunny, but we’re told to make sure our rain gear is tied to our saddles. I am assigned a horse named IRS, which I later find out stands for “I’m Really Stupid.” We’ve been told to expect a 9-1/2-hour trail ride, crossing the pass in about 4-1/2 hours.

The trail is maintained by the U.S. Forest Service, and it would be fair to assume that they spend very little of their budget on actual trail maintenance. My horse walks right on the outside edge of the trail on some of the steepest slope I’ve ever seen. During a pit stop, one of the horses slips and falls on its rider; fortunately, it is a relatively flat spot. We make the ascent about 1/2-hour behind schedule. We stop to put on our rain gear because it looks a little threatening. But as we proceed toward the pass, it starts to snow, instead.

By the time we reach the pass we are in a whiteout at 10,500 feet.

The thing about horses in the mountains is that you ride up and walk down. So down the back side we hike. There were nine hunters in our party, and the outfitter assigned a 10th so we would have an even number. Jim, a retired 64-year-old sheriff, is not physically prepared for the trip. He gets altitude sickness and can’t walk much more than 10 steps at a time. The guy really suffers. We finally make camp after about 10-1/2 hours.

Camp is far and away the most remote place I’ve ever been. I can’t get my bearings and feel completely in the hands of the outfitter and guides. The camp has a corral with a tack tent, cook and dining tent, tents for hunters and guides. We meet our cook Deader, camp jack Eric, and wrangler Josh. We are assigned guides, based upon our assumed ability to keep up with them. Clayton and I are assigned a 23-year-old named Davie Gomez from New Mexico. All of the guides are young and clearly have a passion for hunting elk, which I like. It doesn’t dawn on me that I am putting my safety in the hands of a crew of 20-something thrill seekers. The other guides are Seth, Mike, John and Travis.

After a quick dinner, it is off to the cots, as we will be up at 3:45 for breakfast and hit the trail soon after. Morning comes fast and cold, and I learn an important trick: bring your long johns into the sleeping bag with you.

Davie, Clayton, and I start up to Elk Creek at 5 a.m. I’m now riding a mule named Blondie. Blondie ends up being my favorite. I will take a mule over a horse anytime in the mountains. We ride to the deadfalls, where a massive forest fire swept through back in 1988. Large parts of the landscape still look like a box of charred Lincoln Logs dumped on a table. Some of the trails have been cut out and some haven’t. We make our own most of the time. Did I mention horses and mules can, and will, jump logs?

My riding skills were minimal at the start of the trip, but by the end, I am completely over my fear of horses and riding like an old hand. I’m still amazed at where these animals took us in such vast country. I know Montana is called “big sky country,” but Wyoming is right there. What looks like a 30-minute walk might take 3 hours or more.

Ride, walk, and glass (look through binoculars) is how you hunt elk in this country. Clayton and I agree that he will take the first shot.

We make it to the end of the riding trail through deadfalls and dark timber. After some vertical climbing, we tie the horses up and continue on foot. Our guide leads us to an overlook where we glass the other slope of the valley we just came up. I look up a rockslide just in time to spot a cow elk 200 yards above us. Clayton steps up to a log that provides a perfect shooting support, and a small bull next comes into view, too small to shoot on day one at 8:30 a.m.

Then we hear a bugle; our guide gives a few quick cow calls, and here he comes. With a laser rangefinder, I give Clayton the distance to where the elk should step into view 235 yards away. When he reaches the spot, Davie stops him with a quick cow call, and Clayton drops him with one shot.

At that point, I am thinking, “Elk hunting is easy. What am I going to do with all my time after I tag out?”

Our first elk is on the ground at 9 a.m., but we don’t get back to camp until 6 p.m. First we field dress and quarter the elk, then we get the horses and walk them up. Davie tells us we could have ridden back to camp, got mules, rode back to the elk, and packed it out with the mules. But he is not excited about coming back to a carcass that has been left alone for such a long time. I remember the little joke about bear scat, and smile.

The horses carry the meat but cannot carry the horns and cape, so we walk this out, taking turns putting it on top of our packs. We all sleep very well that night.

The next morning, it is my turn to be the shooter. Back to Elk Creek we go. We see some elk on the way up, but no bulls. We make it back to the same spot as the day before and tie up the horses. We climb back up to the level where Clayton took his elk.

This is where we have our first close encounter with a grizzly. It is eating what is left of the elk carcass and doesn’t seem to notice us, so we keep climbing. At a point about 150 yards above the grizzly, it finally notices us, and then proceeds to work in closer.

It cuts our track, sniffs, and decides to return to the fresh meat. It is then that I realize for the first time how different grizzly bears look in the wild than they do behind steel bars at a zoo.

We climb another 1,000 feet to what Davie calls the plateau. There is about 4 inches of snow on the ground. By the time we work our way out onto the plateau, it is time for lunch and some rest.

After a nap in the snow, I spot a cow moving downslope some distance away. We move up the valley to get a better view and spot a herd. There is a very nice 6x6 or 7x7 in the herd, but they are working their way in the other direction, and I decide against taking a very “iffy” shot. We guess it to be about 600 yards, and the elk is quartering away. My .30-06 has a bullet drop of 53 inches at 500 yards, and I have no idea at 600 yards. We give chase, but one elk stride equals three human strides, and they know where they are going; we don’t. We also have wind to deal with. I still have no idea where those elk went.

We finally give up and decide to get back on track. Davie keeps saying we want to make sure we are back to the horses before dark. We hike back up the plateau, cross to the backside, and drop into Elk Creek. The plan is to drop down to the level of the horses and then work our way back to them. Working our way down, we stop to glass, call and listen. I step on a rock that gives way, and I fall back, hitting my riflescope on a rock. The lens is not broken, but I am sure the scope is off and will not hit where I aim.

We spot some cows and get a bugle. I think it only a matter of time until I see how far off the scope is, but the bull quits bugling. We are losing light, and Davie really wants to get to the horses. Tired, cold and disappointed, we work our way single file to where we think we left the horses, with Davie in the lead, me second, and Clayton behind.

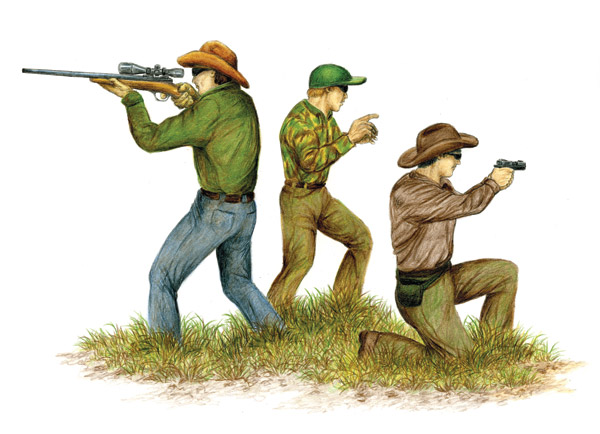

I should mention here that our guide is carrying a sidearm, a Glock chambered in .40 S&W. The .40 is a fine round for defending yourself against a mugger, but like a fly swatter against an 800-pound grizzly. That point didn’t seem to faze our 23-year-old guide when I explained it to him the day before. I had brought a .44 Remington Magnum revolver with me, but the outfitter had talked me into leaving it back at the trailhead. He said it would be heavy, plus I would have my rifle, and all of the guides packed handguns. Besides, they had never had any problems with bears.

We cross an open rockslide area, headed towards a strip of trees. We are within about 10 yards of the trees when Davie yells, “BEAR!”

I hear the familiar sound of a gun being racked (yes, he carried his backup without a round in the chamber). He backpedals into me while I am chambering a round in my rifle (we were asked not to carry rifles with one in the chamber for safety reasons). Before I know it, the bear is a snarling mass of teeth and fur charging straight at us.

We start yelling at the top of our lungs, “Hey bear! Stop bear!” It skids to a halt about 15 yards short of us.

Keep in mind my rifle only holds three rounds and the scope is off. With hindsight, the scope being off was not a big deal. We were told that if you need to shoot a bear with a bolt-action rifle, you wait until you can put the barrel in its mouth before pulling the trigger. Otherwise, you may miss your one shot, not to mention facing a possible $100,000 fine and 5 years in prison for shooting an endangered species. As an afterthought, I guess it would be better than being dead.

Clayton, who shot his elk the day before, doesn’t have a rifle and is carrying rocks at this point. We start to backpedal up the hill to put distance between us and the bear. When the bear starts a second charge, Davie shoots the ground in front of the animal (he said later it was to scare it off). I am focused on the bear’s head, trying to figure out where to aim, because after I hear Davie’s shot I think it is game on. All the while, I am yelling, “DO I SHOOT HIM?” Davie yells back, “No, not yet,” and the bear turns back into the trees.

We turn to go, and out of the corner of my eye I see movement above us. In bear country, apparently, a gunshot is like a dinner bell. A big black and silver grizzly is coming full speed at us. I train my rifle on this one and start yelling, “Hey, bear, get out of here, bear!”

The big bear stops about 35 yards short and starts to circle. In the open, we feel as if we hold a defensible position, but we need to get out of there. With Davie in the lead, Clayton in the middle, and me covering the back, we start to move again. Five steps later, I hear something charging up from behind. I will never forget the sound of that bear huffing and snapping its teeth.

I turn to train my rifle on the bear and slip on the rockslide. This charge stops about 15 yards short, with me scrambling to keep my feet.

I feel as though we are being hunted, that the bears are working in unison. As we move off the rockslide, we see the first bear again about 50 yards below, standing on its hind legs sizing us up. Then it makes a charge up the hill. We are now moving like a swat team. Clayton seems cool and calm. I am ready to shoot as I feel it is coming down to us or them.

We overshoot the horses and have no choice but to go down the mountain, cut the trail we rode in on, and then climb back up to find them. I am lagging behind as we start the climb, coming down from the adrenaline rush, when a herd of elk busts out below us. The elk make quite a commotion running through the timber.

We get to the horses and lead them down to a level spot, saddle up, and head for camp as fast as we dare go. The whole time we don’t know if the bears are still following us or not. An hour and a half later, we descend to the valley floor (camp is at 8,100 feet). Thirty minutes later, we make camp. I can barely stay sitting up in the saddle. Clayton gets off his horse OK, but then he needs to sit for about 10 minutes. I can’t eat. I can only drink water. Surprisingly, I am able to sleep as soon as I crawl into my bag and don’t wake up until 7 a.m.

I skip hunting the next morning, seriously thinking about riding out with the meat run that is leaving camp that morning. But the thought of a 10-hour ride with five mules covered in bear food (elk meat) keeps me at camp.

I do hunt the balance of the trip, four more days, from 5 a.m. to dark each day, and finally tag out two hours before dark on the last day with a small 5x5 elk, giving our camp a total of five bulls and one cow for 10 hunters.

It was an experience of a lifetime, and I wanted to put it down on paper for a number of reasons: One, to get it documented, as I’m sure the more the story gets told, the more the bears will grow in size and ferocity. The second and main reason is to publicly thank God for getting me off that mountain alive. I made a number of promises on that mountain that I plan on keeping.

Steve led us in a group prayer before we left on the trip, and I can’t get his words out of my head. Steve thanked God for giving us dominion over the animals, but I think He just put us on an even footing with some of them.